notable conservationists

Notable Conservationists is devoted to those who influenced Aldo Leopold and to those who were influenced by him. Leopold was very widely read and had many authors to whom he referred to in his writings. In turn, through his own writings, Leopold influenced a heady group of scientists, naturalists and teachers who have continued to spread his teachings, expand upon his thinking and explore new fields of thought and research. These stories will be ever growing as I come across information new to me of which I feel would be of interest to the reader. A thought to keep in mind is that each of these people was influenced by their own mentors and in turn they influenced others. It is a fascinating tapestry of historical tales which paint the journey of how we arrived where we are today in Conservation.

On this page we currently highlight the three people who will be represented at the April 2025 New Mexico Humanities Council program Visionary Voices. For more information on these events click below.

The following overviews were contributed by Stephen Fox

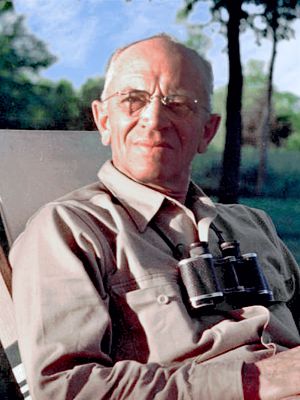

ALDO LEOPOLD

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) was the most influential conservationist of the twentieth century. His book A Sand County Almanac has become one of the most revered texts among naturalists and nature lovers. Leopold wrote it during the last decade of his life, and it stands as his final legacy to us.

He grew up in Burlington, Iowa, on the Mississippi River, in a mansion on top of a hill. As a boy he acquired his outdoor passions by hiking, birding, and hunting with his father and brothers. The river offered duck marshes on its eastern side and woods with quail and partridge to the west. Leopold went east to prep school and then to the Yale Forest School. After receiving his master’s in forestry in 1909, he spent the first fifteen years of his career in the Southwest, mainly New Mexico.

This was perhaps the most important period of his life. He forged a permanent connection to the state by meeting and marrying Maria Alvira Estella Bergere of Santa Fe in 1912. On her mother’s side, Estella was part of the Luna family, one of the powerful old Hispano clans of the territory. It was a conspicuously happy marriage; four of their five children were born during his New Mexico years. Here Leopold began his slow evolution from the selfish, human-centered version of conservation that he had learned at Yale to the radical, nature-centered vision that informed his well-known book The Sand County Almanac. This process began in September 1909 when he shot a wolf and saw her eyes dying, unvanquished, flashing “a fierce green fire.” “I realized then,” he wrote many years later, “and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes.” The encounter left him more skeptical of the prevailing notion, as he put it, “that man is the end and purpose of creation.”In that revised spirit, he conceived the idea of setting aside protected “wilderness areas” within national forests, where human improvements were banned and the land left to itself.

In the spring of 1922, after a month of fighting fires on the Gila National Forest in Grant County, he and some Forest Service colleagues drew the map of the first wilderness area. The Gila Wilderness Area was established two years later, the first of many such areas. In his panoply of originality, intellectual range, writing skill, and lasting influence, Leopold was unmatched among twentieth-century conservationists.

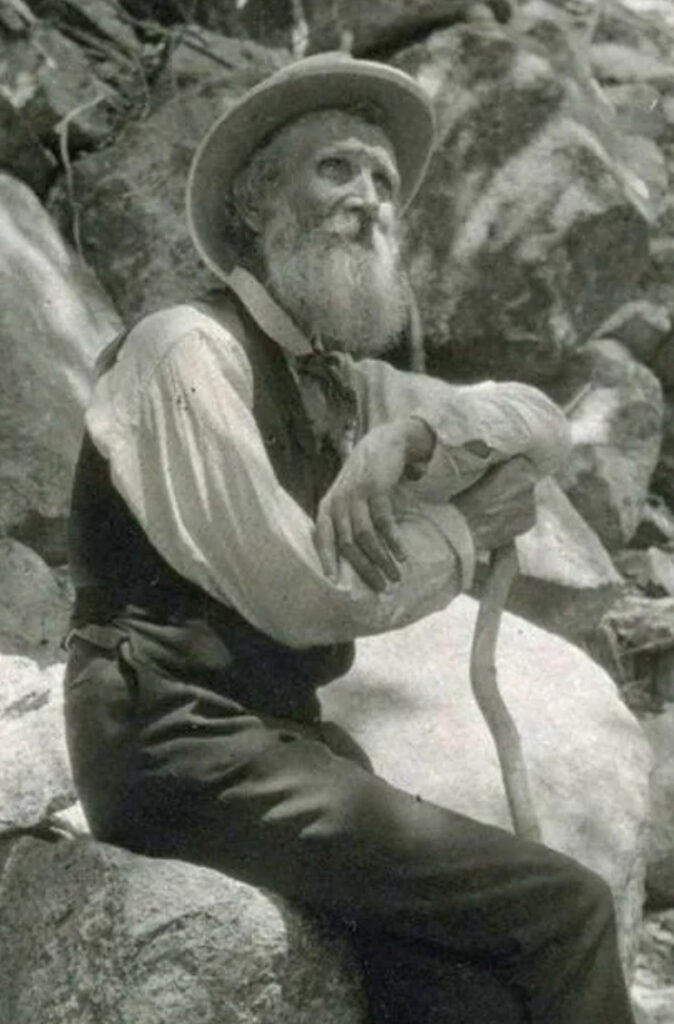

JOHN MUIR

The rapturous accounts of his explorations among the surrounding mountains were published by the best magazines in California and back East. After his marriage, though, he settled into domestic life as a fruit farmer and stopped writing. Yosemite and Robert Underwood Johnson pulled him back. An editor at the Century magazine in New York, Johnson ventured out to California in 1889, looking for unknown writers. “My great discovery here,” he wrote home, “is John Muir.” After camping for two nights in Yosemite, they struck a deal. Muir wanted to establish a new national park in and around Yosemite; so he agreed to write two advocating articles that Johnson would publish in the Century. Now in his fifties, Muir dove into his revived career. Those articles were crucial to making Yosemite the second national park. He published his first book, The Mountains of California, a collection of pieces from the 1870s. Muir also took the lead role in starting a local organization of mountain lovers. In May 1892 they sent an invitation “for the purpose of forming a ‘Sierra Club.’ Mr. John Muir will preside.” Muir was elected president of the club, an office he would hold for the rest of his life. Not a mere figurehead, he settled grumblingly into the routines of administration.

His articles in the Atlantic Monthly became a book, Our National Parks, published in 1901. In six years the volume went through a dozen printings and established Muir as a major voice for the wilderness. His fame as a writer, combined with his base camp in the Sierra Club, made him the most prominent freelance conservationist of his time. “The world we are told was made for man,” he wrote in his journal in 1867. “A presumption that is totally unsupported by facts.” All his later career derived from that central insight.

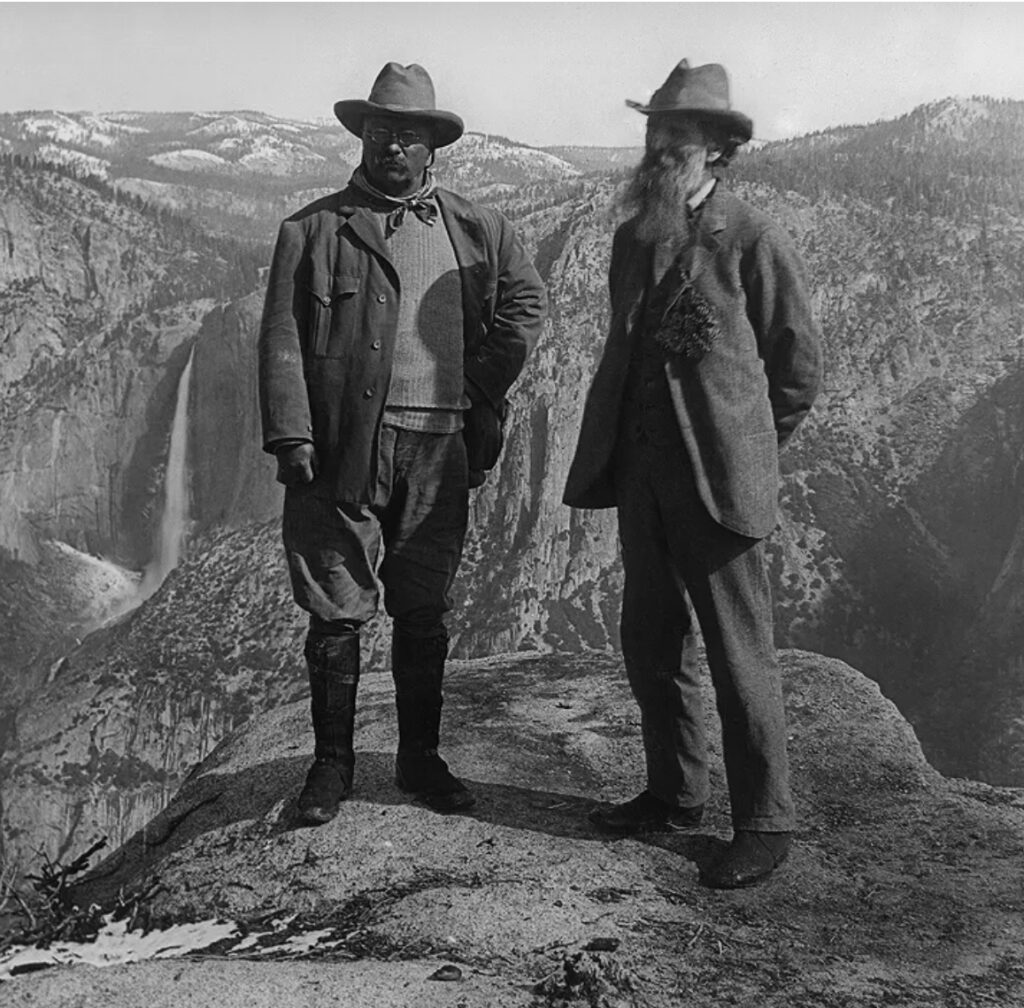

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) was the first conservationist in the White House. A man of stupefying breadth, he was a birder, a writer of natural history, asportsman finding release in the wilderness, a hiker and camper with an esthetic response to the woods—and many other things. He first turned to nature for refuge during an isolated childhood. He studied birds and other small creatures and launched the Roosevelt Museum of Natural History. Conservation began among hunters and fishermen in the 1870s.

TR’s early enthusiasms for birding, hiking, and hunting remained passions all his life. He felt the paradoxical love for wild creatures that he hoped to kill and eat. In 1887 he co-founded the Boone and Crockett Club, limited to sportsmen who had killed three species of American big game “in fair chase.” The group, initially preoccupied with the hunt, soon changed its focus to protecting the animals and their habitats. “When I hear of the destruction of a species,” TR keened, “I feel just as if all the works of some great writer had perished.”

President by accident, he leaped into nature controversies with the aplomb of a man who had killed a grizzly at close range. He knew everyone, read everything, and did not withhold his opinions. During his first year he created thirteen new forest reserves, which soon became national forests. On spring mornings he walked around the White House grounds, noting with a tuned ear the comings and goings of the various bird species.

In the spring of 1903, on a political swing through the West, he asked John Muir to guide him through Yosemite. “I do not want anyone with me but you,” TR made clear. On the first night Muir made him a bed of crisscrossed evergreen boughs. Muir best knew geology and botany, TR birds and animals. Since both men excelled at talking without listening, each could hold forth without treading on the other’s expertise. The day after leaving the valley, TR as urged by Muir extended the Sierra forest reserve all the way to Mt. Shasta, 300 miles to the north. During his last year as president, he gave the opening address at a national conference on conservation. “We cannot, when the nation becomes fully civilized and very rich,” he said, “continue to be civilized and rich unless the nation shows more foresight than we are showing at this moment.”